La cartolina proviene dal Fondo Guerri che ringraziamo per la gentile cortesia; la foto riguarda…

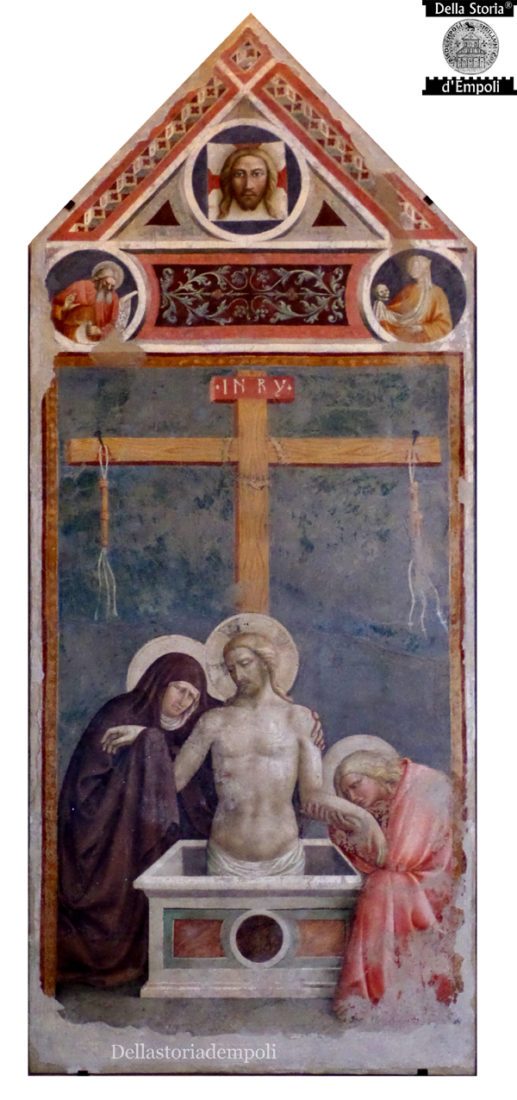

Masolino da Panicale – Imago Pietatis/Cristo in pietà; 1424 ca – English version

Tommaso, also called Masolino da Panicale was Cristoforo Fini’s son

(1383 Panicale? – 1440 ca)

Imago Pietatis, about. 1424

detached fresco; 280 x 118 cm approx.

original place: Church of St. John the Evangelist, today known as the Baptistery.

(inventory Baldini 95)

Origins and history

According to some studies [1] the fresco of Christ in Piety was painted about in 1424 or no later than the first of 1425 [2], the year in which the painter Masolino da Panicale came to Empoli to perform other works in the near church of Santo Stefano degli Agostiniani, such as the frescoes on the right transept, the famous Lunette with the Virgin with Child and two angels on the door of the sacristy, and a cycle known as History of the true cross in Holy Cross’s chapel (or Saint Helena’s chapel).

The fresco was made in the Church of San Giovanni Evangelista, many centuries ago separated from the near church Collegiata di Sant’Andrea and combined with this in 1464, and later used as a baptistery.

The discovery of fresco occurred in not documented circumstances in the 19th century inside the Baptistery, now has become part of the Museum of Sant’Andrea’s Collegiata of Empoli.

The first mention of its existence was made by Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle in 1883 [3] which suggested the attribution to Masaccio and Masolino.

Then Odoardo H. Giglioli in 1906 wrote his wish that the fresco was subjected to « necessary measures to ensure the conservation of the fresco, threatened by moisture’s wall coming from an underground infiltration » [4].

This fresco was detached in 1946, placed on a frame and delivered in Florence at the first exhibition of the restored artwork curated by Ugo Procacci; in 1956 it was placed in the new (and current) location of the Museum.

It was delivered to the second exhibition of the detached frescoes in Florence in 1958 [5], while in 1985 it was restored in a florentine workshop under the supervision of Alfio Del Serra.

In 1990 it was replaced in its original location, that is the Baptistery, where you can admire its magnificent beauty.

Description and attribution

Its rectangular shape is crowned by frescoed cusp.

It’s essential, made by simple but intense construction: in the middle of scene there is a Christ, designed only his middle upper part of his body, painted by a good anatomy, emerging from a marble sarcophagus designed by glimpse.

There are the Madonna on the left side, while St. John Evangelist on the right kneeling and kissing the left weak arm of Christ; his body was drawn as a deep style through to the play of lights and shadows, and especially looking at the folds of garments.

The cross dominates the scene, and two pending Roman flagella appear obvious and still attached to nails; it simulates very well a very realistic scene using these symbolic elements, able to witness a deeply martyrdom of flogging before the final torture.

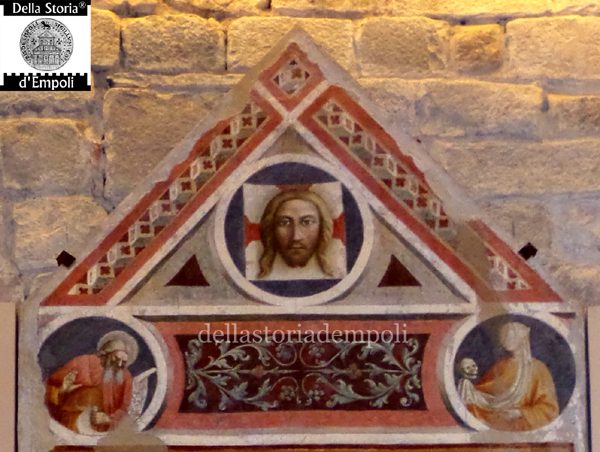

The above cusp has miraculously maintained a multicoloured despite « the ravages that time and neglect have brought the painting to a great artist dedicated all his art skills and all poesy of his soul », as said Odoardo H. Giglioli. [6].

The cusp has a definite geometrical and compositional structure: at the top there are two sides made of aligned and overlayed cubes, all their sides are pierced by windows called “quadrilobate”; it’s a good job of prospect, however in the top it doesn’t respect a correct symmetry due to a cube rotated in the same direction as the left side. In the center of the cusp there is a round including inside a Holy Face.

Below the cusp there’s a horizontal floral’s pattern frame, interrupted to extremes by two rounds: on the left there’s the Prophet Isaiah who predicts the coming of Christ; on the right there’s an acephalous body because his head was covered by a small piece of plaster, but should be the prophet Ezekiel because he receives a vision of the death and resurrection of Christ.

Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle [7] in 1883 attributed the fresco to a collaboration between Masolino and Masaccio; after him, Jacob Burckhardt [8] and August Schmarsow [9] attributed the exclusive work to Masaccio, while Guido Carocci [10] in 1899 attributed the work to Masolino. Also Bernard Berenson [11] in 1902 attributed the work to Masolino for these reasons:

Original phrase:

«un tipo trecentesco che non si ritrova mai in Masaccio e che appare due volte sole nell’opera di Masolino: nella Risurrezione di Tabita della Cappella Brancacci e nel quadro di Monaco»

Translated version:

« a fourteenth-century model that you never found on Masaccio and it appears only twice in the works of Masolino: in the Resurrection of Tabitha in Brancacci’s Chapel and in the painting of Monaco »

A few years after (1905) it was discovered a document that reports a payment to Masolino in 1424 for some frescoes made in St. Helena’s chapel, owned by the Cross’s Company located in the near St. Stephen’s church in Empoli:

Original phrase:

«Detta cappella di sopra nominata dhella Compagnia la fece dipingere per infino addì 2 novembre MCCCCXXIIII pagano al Maso di Cristofano dipintore da Firenze fiorino settantaquattro d’oro come apparisce in su gli antichi nostri libbri» [12]

Translated version:

« The same chapel called dhella Company was painted till 2 November MCCCCXXIIII and pay to Maso di Cristofano painter from Florence seventyfour golden florins as it appears in our ancient books »

In 1908 Pietro Toesca attributed the fresco’s authorship to a joint collaboration between Masaccio and Masolino, While the latest experts and art critics agree that’s attributed to Masolino’s artwork, such a as Venturi (1911), Lindberg (1931), Salmi (1930), Longhi (1940) and many other contemporaries.

Many elements and geometries painted in the fresco will help to read some changes under way in that time in the Florentine painting school, especially doing a comparative analysis referring to the masterpiece done in Brancacci’s Chapel together Masaccio.

The vision of this fresco instils a sense of purity and causes a sense of deep feeling impressed by the scene; I suggest you visit it, and I hope that you try the same details emotions.

***

↖ Digital Guidebook of Museum of Sant’Andrea’s Collegiata of Empoli

↖ Index of EMPOLI ARTISTICA

Notes and references:

[1] Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea a Empoli, R. C. Proto Pisani, series “Piccoli Grandi Musei”, Firenze, Edizioni Polistampa, 2006, pag. 42;

[2] Il museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea in Empoli, A. Paolucci, Firenze 1985, pag. 92-93;

[3] Storia della pittura in Italia dal secolo II al secolo XVI, volume II, Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle, Firenze 1883, pag. 264;

[4] Empoli Artistica, Odoardo H. Giglioli, Lumachi Editore, Firenze 1906, pag 42-43;

[5] Firenze, Forte di Belvedere, april-may 1958;

[6] Empoli Artistica, Odoardo H. Giglioli, Lumachi Editore, Firenze 1906, pag 42-43;

[7] Storia della pittura in Italia dal secolo II al secolo XVI, volume II, Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle, Firenze 1883, pag. 264;

[8] Der Cicerone, vol. II, part. III, Jacob Burckhardt, Leipzig pag. 643;

[9] Kunsthistorische Gesellshaft fur photographische Publikationen, August Schmarsow, Siebenter, Jahrgang, 1901;

[10] La Galleria della Collegiata d’Empoli, G. Carocci, in “Le Gallerie Nazionali Italiane. Notizie e documenti”, Roma 1899, pag. 334;

[11] Quelques peintures mèconnues de Masolino da Panicole, B. Berenson, Gazzette de Beaux Arts, vol. I, 1902, pagg. 89-99;

[12] Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea a Empoli, R. C. Proto Pisani, collana “Piccoli Grandi Musei”, Firenze, Edizioni Polistampa, 2006, pag. 42;

Images:

published in accordance with the decree-law “Franceschini” May 31, 2014 Art. 12 paragraph 3:

Essential bibliography

Empoli. Itinerari del Museo, della Collegiata e della Chiesa di Santo Stefano, R. C. Proto Pisani, collana “Biblioteca de Lo Studiolo”, Calenzano (Fi), Becocci/Scala, 2005;

Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea a Empoli, R. C. Proto Pisani, collana “Piccoli Grandi Musei”, Firenze, Edizioni Polistampa, 2006;

Empoli, il Valdarno inferiore e la Valdelsa fiorentina, R. C. Proto Pisani, collana “I Luoghi della Fede”, Milano, Mondadori, 1999;

Empoli. I luoghi e tesori della storia, A. Naldi, P. Pianigiani, L. Terreni, Editori dell’Acero, Empoli 2012;

La Collegiata di Sant’Andrea a Empoli, la cultura romanica, la facciata, il restauro – Galletti, Moretti, Naldi, Edizioni dell’Erba, Fucecchio, 1991;

Chiese, cappelle, e oratori del territorio empolese, W.Siemoni, Editori dell’Acero, S. Croce sull’Arno, 1997;

Il museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea in Empoli, A. Paolucci, Firenze 1985;

Empoli, una città e il suo territorio, W. Siemoni e M. Frati, Editori dell’Acero, Santa Croce sull’Arno, 1997;

Empoli: città e territorio. Vedute e mappe dal ‘500 al ‘900, AA.VV., Editori dell’Acero, Santa Croce sull’Arno 1998;

Questo articolo ha 0 commenti